RefracTeD Reflections

Perceptions of gender Inequality in Dutch Energy Organisations

Kirsten Mallant

May 2023

Citation

Mallant. K. (2023) Refracted Reflections. Perceptions of Gender Inequality in Dutch Energy Organisations. Thesis TU Delft & 75inQ

Perceptions of gender Inequality in Dutch Energy Organisations

Management summary

| Reference | Refracted Reflections (Summary), Mallant, K. (2023) |

| Date | 01-06-2023 |

| Author | Kirsten Mallant |

| Supervision | Dr. M. (Mariëlle) Feenstra, 75inQ Dr. J. (Jenny) Lieu, Organisation and Governance |

CONTEXT

Objective: labor shortages on the energy labor market

The increasing tightness on the Dutch labor market is becoming increasingly worrying, with no fewer than 449,000 vacancies in the autumn of 2022, according to Statistics Netherlands (CBR) (1). This shortage is mainly caused by the aging of the population and has consequences for almost all sectors in our country (2). At the same time, the consequences of climate change are becoming increasingly urgent and clearly visible in the Netherlands. To do something about this, the Dutch government has set the target of reducing CO2 emissions by 49% in 2030 and 95% in 2050 (3). This requires an accelerated energy transition and it is expected that this will create more jobs in the sustainable energy sector. The ‘Internationaal Agentschap voor Hernieuwbare Energie’ (IRENA) predicts that the number of renewable energy jobs worldwide will grow from 10.3 million in 2017 to 29 million in 2050 (4). To meet this need and promote the emancipation of women, it is important that the Dutch energy labor market expands. There is a lot of progress to be made regarding gender equality. The Netherlands currently ranks 28th when it comes to gender equality according to the World Economic Forum (5). Dutch women still earn 13% less per hour than men (6%), and almost half of Dutch women are financially dependent on a partner or the government (7%). It will take at least 88 years before there is gender equality in our country (8).

The energy sector is one of the least gender-diverse industries in the Dutch economy (9). Women make up 47% of the total workforce (10%), but women represent only 22% of the workforce in the Dutch energy sector (11%). In addition, women are now leaving management positions more often than ever before, further widening the gender gap in senior positions (12). Despite efforts to promote gender equality and indirectly address the labor shortage, there remains room for improvement.

Perceptions of factors regarding gender equality in the energy sector

In my master thesis for my Master Management of Technology at TU Delft, I conducted research into perceptions of gender inequality in the Dutch energy sector, because they can provide insight into how problems are experienced and interpreted. Perceptions can be influenced by personal factors, such as experiences, knowledge and environment, and can lead to different interpretations and priorities of actors. By examining the perceptions of employees in Dutch energy organizations, it can be better understood which aspects of gender inequality are perceived by them and which intervention points need to be addressed to promote change.

Three Prisms

The concept of ‘prisms’ used in this study refers to different perspectives or points of view through which gender inequality can be perceived and interpreted. Here is a more detailed explanation:

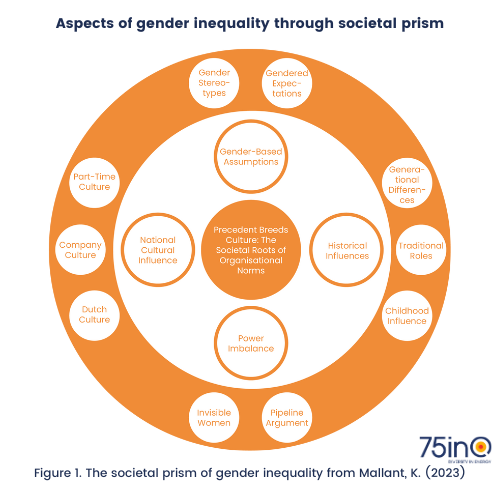

- The Societal Prism: This prism is about the broader socio-cultural context. Think of the set of ideas, norms, values, and rules that exist in society about gender roles. For example, if someone thinks that gender inequality is mainly caused by cultural norms and values, he/she looks at the problem through this prism.

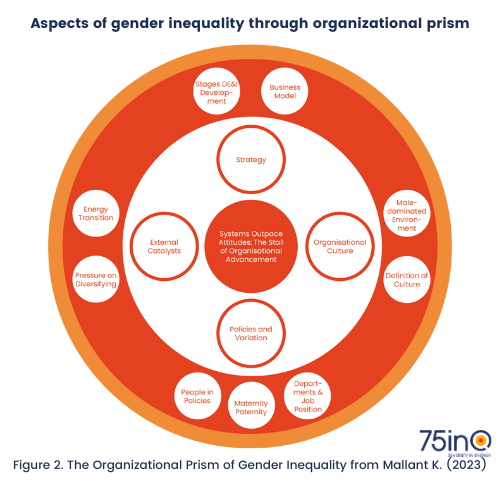

- The Organizational Prism: This prism focuses on the internal structure and practices of specific organizations, in this case an energy company. It concerns the rules, policies, work practices, and internal culture of the organization. When someone believes that unequal rules or practices within an organization contribute to gender inequality, they are looking through the “organizational” prism.

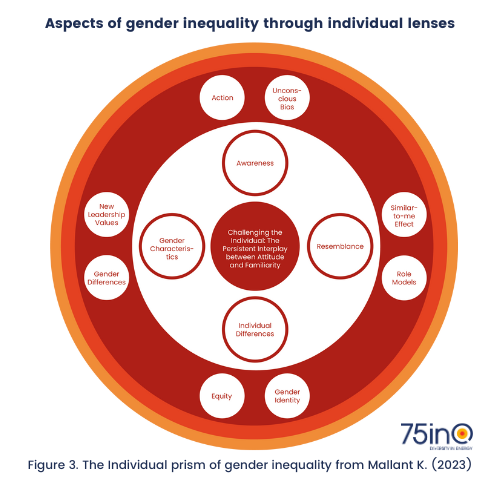

- The Individual Prism: This prism refers to people’s individual beliefs, attitudes, experiences, and perceptions. For example, if someone believes that men and women are fundamentally different by nature and that this leads to inequality, then this person views the problem of gender inequality through the “individual” prism.

The research examines how these three ‘prisms’ influence the perception of gender inequality. The idea is that the way people view gender inequality, and the solutions they propose, can be strongly influenced by which of these ‘prisms’ they use to look at the problem. By mapping these different perspectives, the research can provide a deeper understanding of the complex nature of gender inequality and how it is experienced and understood in different contexts.

RESEARCH QUESTION

In a global survey of 16,500 employees from different industries, 95% of participants reported that their employers have taken actions to create more diversity, but only 25% of diverse employees have experienced the benefits of these initiatives (13). This difference is explained by a difference in perception: the decision makers (often older men) do not always have a good understanding of the severity and nature of the problems surrounding diversity. As a result, they often do not select the most effective diversity initiatives. Several other studies (14) (15) support this idea and show that perceptions of gender inequality are complex and vary widely. A lack of understanding of the causes of gender inequality can hinder progress towards equality.

The main research question is therefore: How do perceptions of gender inequality among employees in Dutch energy organizations arise from the interaction between social, organizational and individualistic aspects, as well as personal factors?

Research method

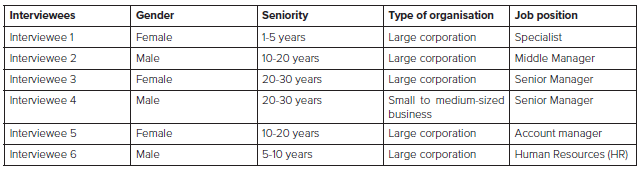

To answer my main research question, I used a qualitative, transdisciplinary approach in my research method. This means that the research combines different methods to gain an in-depth picture of the problem. These methods include observing events, conversations with researchers, a survey among 74 participants, and in-depth interviews with six gender experts and six employees from the Dutch energy sector. The participants represent a wide range of functions, experience levels and genders within various Dutch energy organizations. The demographic characteristics of the employees interviewed can be found in Table 1. This broad range is important to get a good idea of the different perceptions of gender inequality in the sector.

Table 1. Interviewed employees with their gender, seniority, type of organisation and job position

RESEARCH FINDINGS

To summarize the results of my thesis, I have identified three central themes within the different prisms – the societal, the organizational and the individualistic:

the societal prism

The central theme of the societal lens, entitled “Precedent creates culture: the societal roots of organizational norms,” emphasizes the role that long-standing societal customs and expectations play in shaping gender inequality within Dutch energy organizations. The research shows that historical patterns and deeply entrenched societal norms continue to influence the work environment and employee attitudes towards gender equality.

De organizational prism

The central theme of the organizational lens, entitled “Systems trump attitudes: The standstill of organizational progress,” highlights the complex relationship between structural problems and persistent attitudes that contribute to the perpetuation of gender inequality within organizations. Structures within organizations have often changed, but people continue to behave as before.

The individual prism

The central theme of the individualist lens, entitled “Challenge of the Individual: The Persistent Interplay of Attitude and Familiarity,” suggests inherent biases toward different genders. The analysis shows that, among other things, general statements about gender, informed by prejudices and the interaction between awareness and familiarity, contribute to perceptions of gender inequality.

In summary, the three lenses highlight different aspects of the perception of gender inequality and show that society, organization and individuals all play a dual role in this perception. Each individual perceives the problem from a different perspective, influenced by their unique position in an organization or society. Each individual’s unique perceptions of gender inequality underscore that the core of this problem lies in the broader system, including social norms, organizational structures, and individual biases. That is why the motto ‘don’t fix the women, fix the system’ is essential: trying to adapt women to an inherently unequal system, without addressing these deep-rooted causes, can actually further reinforce existing inequalities.

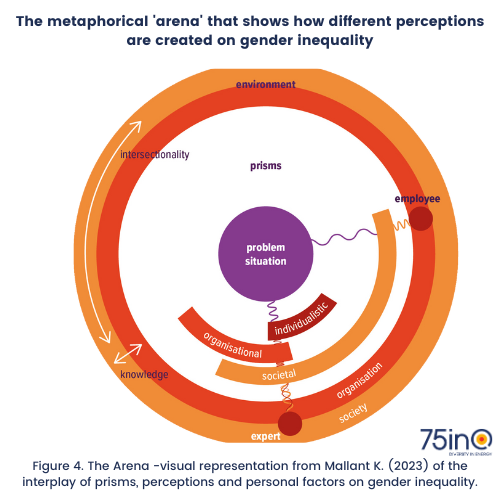

Conclusion: the arena

The research tried to understand how perceptions of gender inequality form among employees in Dutch energy organizations. To do this, a new framework called “the arena” has been developed. This framework helps to show how perceptions of gender inequality are intertwined and where opportunities lie to bring about change.

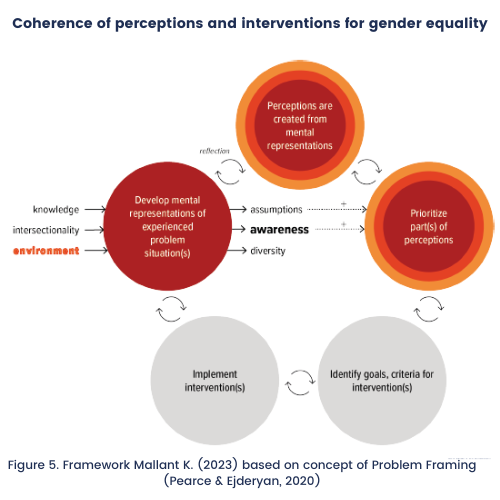

In this framework, gender inequality is presented as the core at the center of an arena. Around this core there are various ‘prisms’ that represent the social, organizational and individual aspects. Each individual looks at the core through these lenses, resulting in different perceptions of the problem. These perceptions are further influenced by the individual’s position in the arena and his/her personal knowledge and intersectional experiences (such as their experiences based on their gender, race, class, etc.).

The framework shows that these different perceptions of gender inequality are shaped by mental images of the experienced problem situation. These mental images are shaped by the individual’s environment, his/her knowledge and intersectionality. They influence how the individual thinks about the problem, for example in terms of assumptions, awareness, and the extent to which they value diversity. These mental images ultimately determine how the individual views the problem of gender inequality and which aspects he/she considers most important.

recommendations for the energy sector

- The research has shown that many Dutch energy organizations fail to give a voice to those who actually experience and recognize gender inequality. Instead, the voices of those with the strongest assumptions are often heard the most. An important finding is that many people are not against equality, but simply lack the insight to consider it a priority.

- The fact that each individual perceives the problem from a unique perspective, influenced by their position in an organization or society, suggests that the roots of gender inequality are embedded in the broader system. So trying to “fix” women by encouraging them to change their behavior or attitudes to fit a system that is inherently unequal would not address these root causes. Instead, it could further reinforce existing inequalities. In contrast, a systemic approach, which seeks to change societal norms, organizational structures and individual biases, would address these root causes and thus be more effective in reducing gender inequality.

- Because experience plays an important role in driving awareness about gender inequality, companies can develop interventions that allow employees to experience what it is like to experience inequality. This can help them become more aware of the problem.

The research has further shown that visualizing the various perceptions within a company helps to understand differences between various groups, such as managers and other employees. This insight can contribute to evaluating and improving current interventions. By outlining an “arena” within your own organization, you can create clarity and focus for the pursuit of gender equality. It provides a useful tool for navigating the complexity of this issue.

Furthermore, the research illustrates that your gender or position in itself does not determine your perception of gender inequality. Awareness alone is also not enough to set priorities; action is needed. For example, in 1975, 90% of Icelandic women went on strike for a day to protest against wage inequality and unfair working practices. This action helped to prioritize the issue of gender inequality and led to the introduction of equal pay laws in Iceland.

This research contributes to the broader discussion on transdisciplinary methods by highlighting the importance of individual perceptions in understanding social problems such as gender inequality. It shows how this approach can lead to a deeper, more complete understanding of the problem that is academically rigorous but also takes into account practical perspectives.

bibliography

- CBS. (2023). Vacatures. Centraal Bureau Voor de Statistiek. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-arbeidsmarkt/vacatures

- Lambregtse, C. (2022, June 28). De krappe arbeidsmarkt: wat zijn de oplossingen? SER. https://www.ser.nl/nl/Publicaties/krappe-arbeidsmarkt-oplossing

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat. (2022). Klimaatakkoord | Klimaatakkoord. https://www.klimaatakkoord.nl/

- IRENA. (2019). Renewable Energy A Gender Perspective. https://www.irena.org/publications/2019/Jan/Renewable-Energy-A-Gender-Perspective

- World Economic Forum. (2022). Global Gender Gap Report 2022. www.weforum.org

- CBS. (2022b). Beloningsverschillen tussen mannen en vrouwen; bedrijfstakken https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/81920NED/table?fromstatweb

- CBS. (2022c). Emancipatiemonitor 2022. https://longreads.cbs.nl/emancipatiemonitor-2022/werken-en-zorgen/

- Women Inc. (2022). Berekening “bijna 90 jaar” voor communicatie.

- Creusen, A., Feenstra, M., & Povee, A. (2023). Bewust en Bekwaam – Een energietransitie die werkt voor vrouwen. In 75inQ.

- CBS. (2022a). Arbeidsparticipatie naar leeftijd en geslacht. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-arbeidsmarkt/werkenden/arbeidsparticipatie-naar-leeftijd-en-geslacht

- Feenstra, M., & Creusen, A. (2021). Rapportage vrouwen in de energietransitie. https://www.topsectorenergie.nl/sites/default/files/uploads/HCA/Vrouwen_in_de_energietransitie_75inQ_TopsectorEnergie.pdf

- McKinsey, & LeanIn.Org. (2022). Women in the Workplace 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/women-in-the-workplace

- Krentz, M., Dean, J., Garcia-Alonso, J., Tsusaka, M., & Vaughn, E. (2019). Fixing the Flawed Approach to Diversity. BCG. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/fixing-the-flawed-approach-to-diversity

- Colley, L., Williamson, S., & Foley, M. (2021a). Understanding, ownership, or resistance: Explaining persistent gender inequality in public services. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(1), 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/GWAO.12553

- Benschop, Y., & Verloo, M. (2006). Sisyphus’ Sisters: Can Gender Mainstreaming Escape the Genderedness of Organizations? Journal of Gender Studies, 15(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589230500486884