mapping the mindsets of dutch muncipal policy workers on mitigating energy poverty in the gender-just energy transition

an exploratory q study

Hanna Kreuger

January 2023

Citation

Kreuger, H. (2023) Mapping the mindsets of dutch muncipal policy workers on mitigating energy poverty in the gender-just energy transition. An exploratory Q study – 75inQ

Mapping the Mindsets of Dutch Muncipal Policy Workers on Mitigating Energy Poverty in the Gender-just Energy Transition

Summary & recommendations

| Reference | Samenvatting stageopdracht 2021-2023 |

| Date | 20-01-2023 |

| Author | Hanna Kreuger |

| Supervisors | Mariëlle Feenstra, PhD, 75inQ Tineke van der Schoor, PhD, Hanzehogeschool |

Figures

Recommendations

- Municipalities must be given the knowledge and capacity to sort out the complexity of energy poverty. This can be done through access to data, workshops, etc. (the second recommendation builds on this)

- Communication and knowledge sharing (facilitated by the government or in another way) can help accelerate the approach to energy poverty and prevent every municipality from having to reinvent the wheel itself. One solution for the entire Netherlands is also not possible, but similar municipalities (not per region, but for example based on number of inhabitants or types of housing) can work together to save time.

- The SPUK funds can be tightened with requirements and more guidance from the government, so that it is easier for municipalities to create a roadmap and reduce spatial injustices due to differences between municipalities.

- The approach to energy poverty is grouped under different departments in different municipalities. A break the silos approach (not addressing the problem under the social domain, sustainability, etc., but tackling it municipally-wide) can lead to better results.

Context

In autumn 2022, the Netherlands had approximately 550,000 energy-poor households according to TNO researchers (1). Of this number, an estimated 140,000 are invisible: households that still pay their energy bills, but have had to adjust their energy consumption behavior in such a way that their living comfort is affected. Energy poverty is a buzzword that has received a lot of attention in the Netherlands from politicians and society due to the corona crisis (2) and the war in Ukraine (3). On the one hand, people spent more time at home due to the pandemic, which increased household energy use. On the other hand, energy prices rose due to pressure on Russian gas supplies. However, before these events, energy poverty was already a growing problem for many households in the Netherlands.

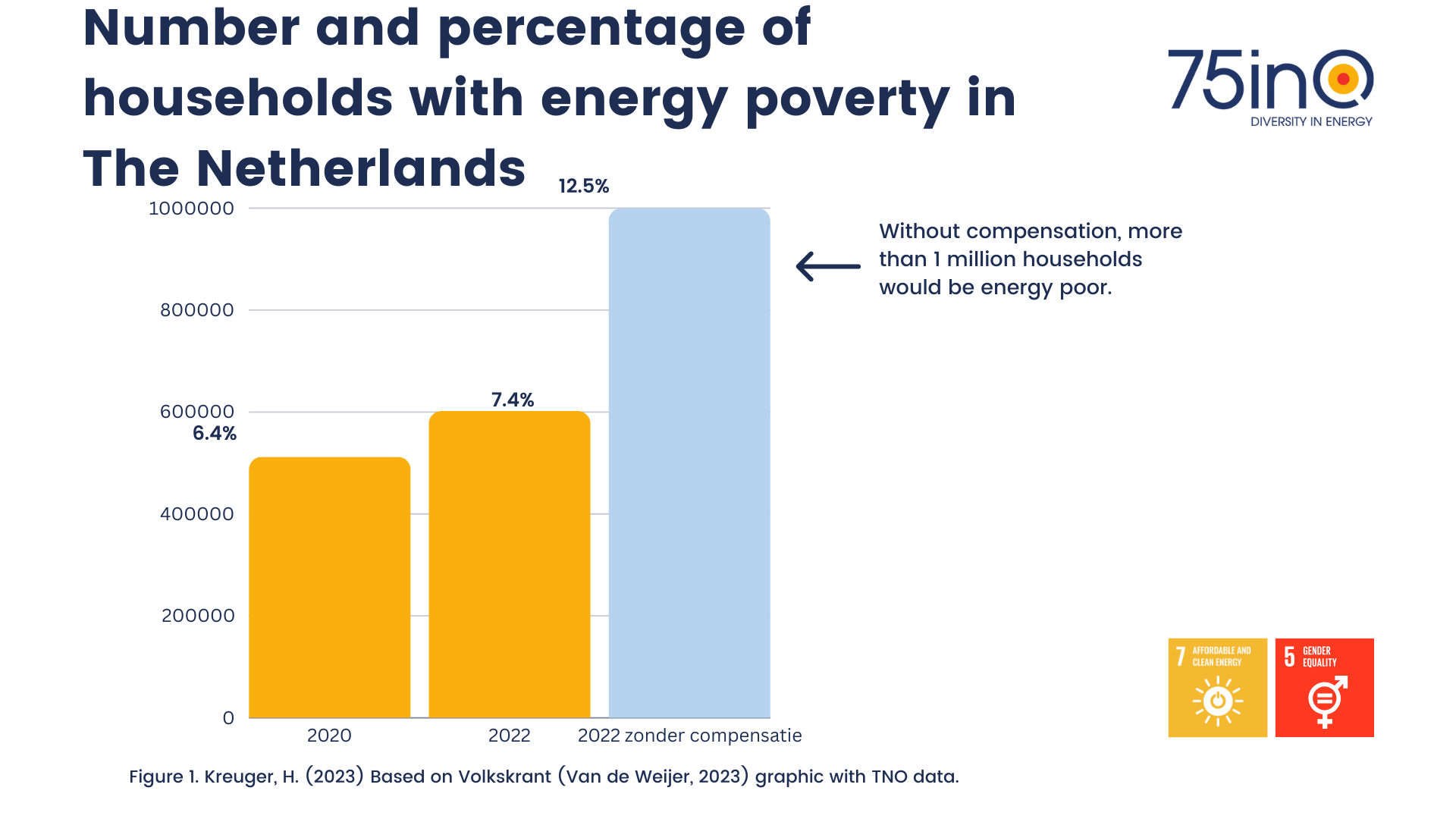

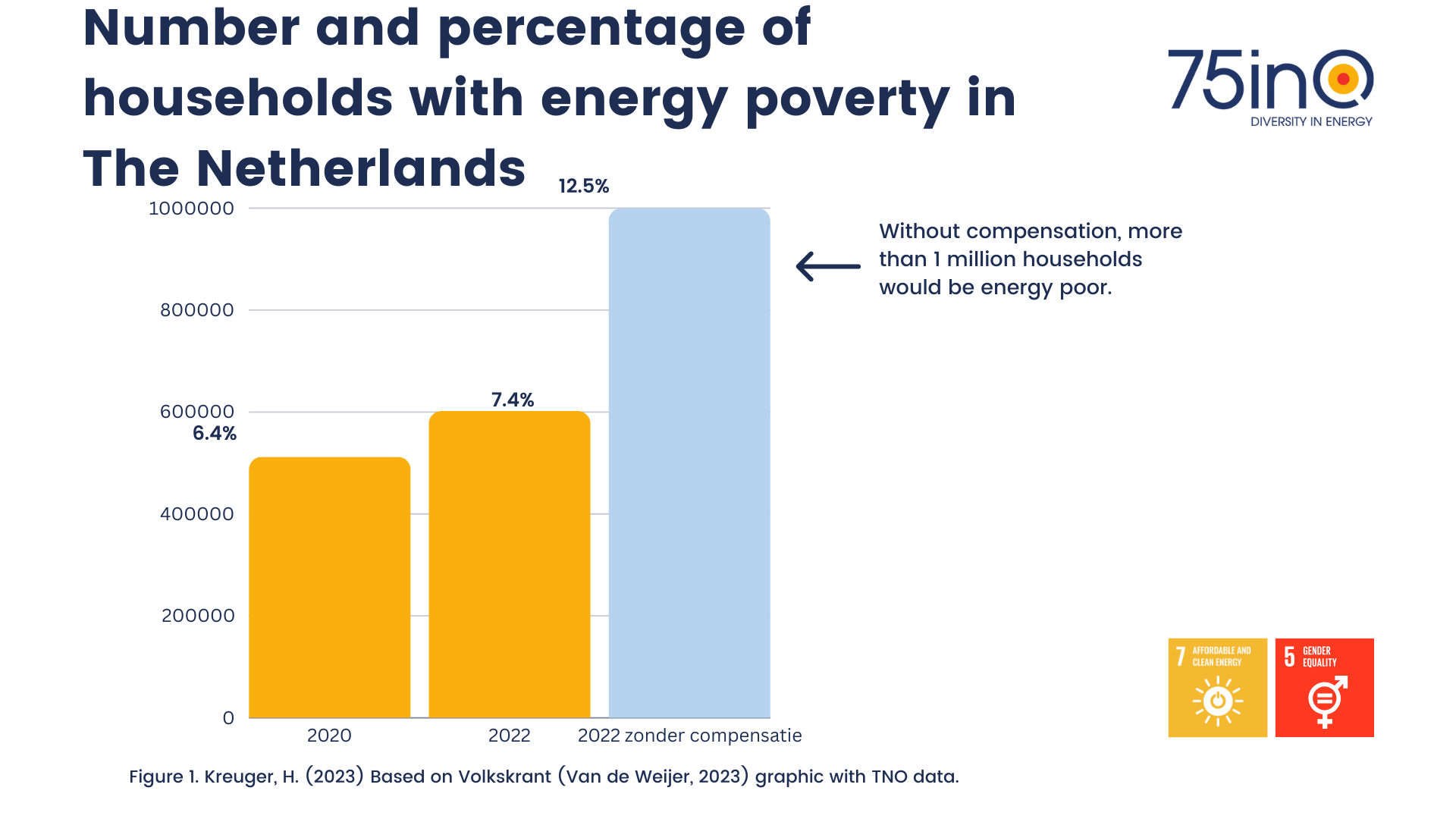

The discount on energy bills in November and December 2023, the energy surcharge and the price ceiling have ensured that the number of energy-poor households has not doubled. These three national emergency solutions, fueled by the growing political attention to energy poverty, have put out fires (4), but according to TNO (Figure 1), the Netherlands still has 602,000 energy-poor households (5). These households are certainly helped by the above policy, but need additional help to be able to escape energy poverty in a future-proof and structural way.

Connection to the energy transition

Energy poverty is not an isolated challenge: the Netherlands faces an even bigger task, namely the energy transition. People who have difficulty paying their energy bills are less likely to participate in the energy transition. A sustainability gap is emerging where those who can invest in the energy transition benefit from lower energy costs, while those who cannot are confronted with high energy costs and little opportunity to adjust their energy consumption behavior. The financial and social disadvantage that this group has in society will increase as the transition progresses.

Gender

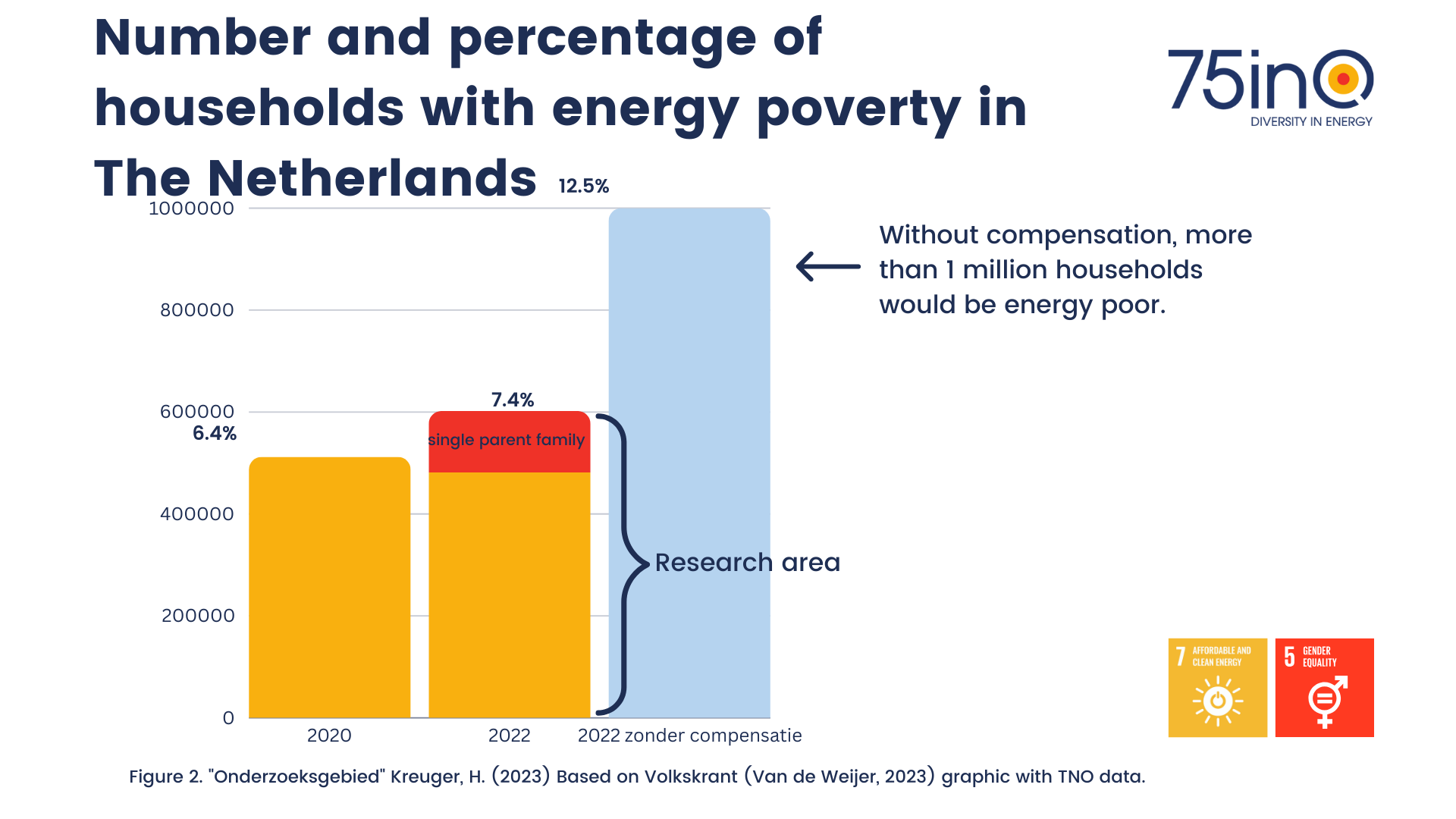

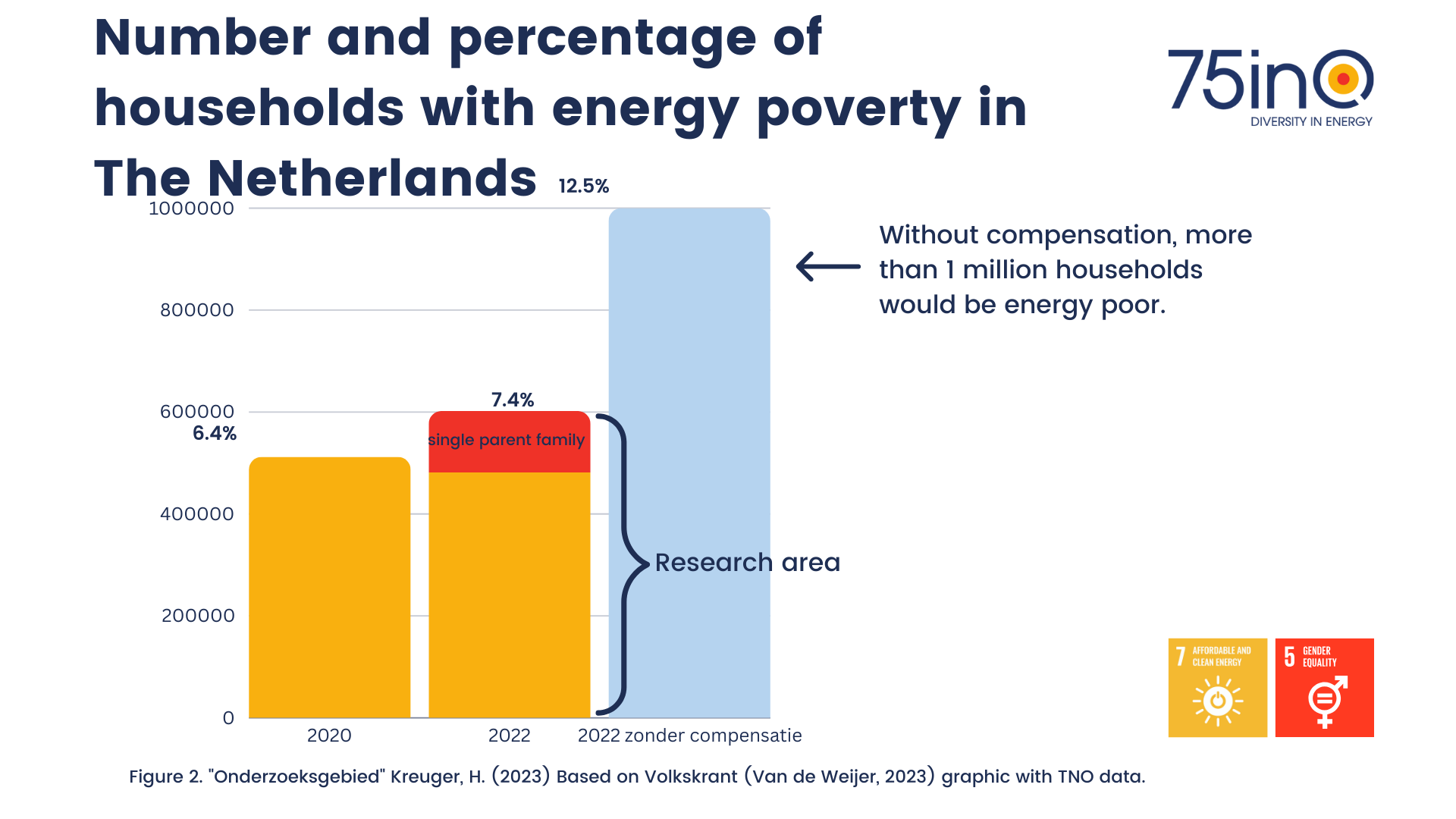

One way to analyze this social complexity is through a gender lens. That is, if you look more deeply at the characteristics of energy-poor households in the Netherlands, you will see, for example, that 1 in 5 households are single-parent families (6). These are predominantly families with a single mother who has a caring role for dependent family members (7). Financially, women are more likely to be affected by (energy) poverty due to the persistent wage gap between men and women (8). There are also physiological aspects. For example, women are more likely to suffer from cold or heat due to a different body temperature regulation than men (9). In addition, many women live longer than men, leaving many widows alone with bills and a lower income than their husbands(10). This does not mean that energy poverty is exclusively a women’s problem, this way of studying complexity can also be done from other perspectives such as ethnic background. It does show that energy poverty as a socio-economic problem strengthens and increases structural inequality in society. However, the three national emergency solutions do not reflect this: the energy bill discount was for everyone, the energy surcharge is calculated based on income and the price ceiling on (large) household consumption.

Policy decentralisation and multilevel governance

The Netherlands has a high degree of policy decentralization and ‘multilevel governance’: the distribution of policy implementation from national governments to municipalities. Dutch municipalities are now taking the initiative to further tackle energy poverty with specific benefits (SPUK) (11). These SPUK funds offer municipalities policy freedom and therefore the opportunity to develop local, tailor-made solutions that tackle energy poverty at its root cause and make it possible for larger groups of households to participate in the energy transition. The risk of the SPUK funds is spatial injustice because of the freedom of municipalities to develop their own interventions: households can receive different support per municipality. For example, households in one municipality receive an increased energy allowance, while households in the neighboring municipality only receive LED lights or draft excluders.

Research

The remaining 602.000 households living in energy poverty therefore have a much more complex identity than the policy currently reflects (Figure 2). Through literature research, my research further explains the social complexity, such as the fact that a fifth of energy-poor households are single-parent families headed mainly by women. It also summarizes which local policy initiatives already exist to tackle energy poverty.

With the policy freedom that the SPUK funds offer municipalities in mind, it is important to question municipal policy staff: how do they actually see energy poverty and what policy choices do they make? This influences the nature of municipal interventions to combat energy poverty.

The main research question is therefore: What are the most common mindsets of Dutch municipal policy officers about tackling energy poverty to implement a gender-just energy transition?

Mindsets

To answer the main research question, I used the Q method in combination with interviews of respondents. Respondents cluster sets of statements around a topic. The Q method can discover subjectivity and therefore groups of like-minded people in a dataset. What makes the method unique is that statements are not assessed individually on a Likert scale, for example, but are placed together on one table. From the survey in which policy officers sorted statements about tackling energy poverty at the municipal level and (afterwards) conducted interviews, two types of mindsets were identified among municipal policy officers responsible for energy poverty policy: the institution focusers and the explorers:

- The institution focusers tend to agree with statements that portray less responsibility for municipalities. For example, the responsibility for tackling energy poverty lies more with housing associations and the national government. At the same time, the institution focusers emphasize the overarching goal: the energy transition.

- The scouts put statements about further defining and investigating energy poverty higher on their priority list. Scouts emphasize the importance of a local perspective on energy poverty and clearly disagree with a financial approach alone.

Both mindsets are positive about energy poverty reduction initiatives such as energy coaches and energy fixers. They also agree that policy officers do not necessarily have to be a direct reflection of the diversity (for example in gender, ethnicity, etc.) of residents in their municipality.

Other findings

In addition to the two mindsets, the research also identifies the following findings:

- Both mindsets support the use of energy coaches and energy fixers. These are people (unpaid and paid, respectively) who can explain to residents how to use their energy efficiently (coach) and install energy-saving solutions (fixers).

- Both mindsets pay attention to matching opportunities. Projects are critically examined at the various goals that must be achieved and whether there is an overlap in topics and approaches.

- There is an awareness of decentralization & multilevel governance. That is to say, the growing responsibility of the municipalities and the fragmentation of policy is noticed by policy staff. This was mainly mentioned in the interviews and was received both positively and negatively by the interviewees.

- Statements that explicitly mention gender and/or ethnic background are received with confusion. In the interviews in particular, policy staff responded with confusion to the statement where gender and/or ethnic background was mentioned. It was not always clear what this has to do with energy poverty. In the results, the statements ended up at the bottom of the priority list for both groups (lower for the institution focusers than for the explorers).

Recommendations

- Municipalities must be given the knowledge and capacity to sort out the complexity of energy poverty. This can be done through access to data, workshops, etc. (the second recommendation builds on this)

- Communication and knowledge sharing (facilitated by the government or in another way) can help accelerate the approach to energy poverty and prevent every municipality from having to reinvent the wheel itself. One solution for the entire Netherlands is also not possible, but similar municipalities (not per region, but for example based on number of inhabitants or types of housing) can work together to save time.

- The SPUK funds can be tightened with requirements and more guidance from the government, so that it is easier for municipalities to create a roadmap and reduce spatial injustices due to differences between municipalities.

- The approach to energy poverty is grouped under different departments in different municipalities. A break the silos approach (not addressing the problem under the social domain, sustainability, etc., but tackling it municipally-wide) can lead to better results.

In the short term, the research shows where the bottlenecks are in tackling energy poverty; current national policy is inadequate for more than half a million households and the complex nature of these households cannot yet be sufficiently appreciated by policy staff. That doesn’t mean they don’t recognize the complexity. The explorers (more than the institution focusers) do see complexity, although not explicitly based on gender. However, a combination of the time pressure and urgency of this problem with a shortage of capacity is the reason that this cannot be worked out and implemented calmly and structurally.

In the longer term, the mindsets show subjectivity among municipal officials and in the policy cycle. That is not news, but it is extremely interesting that these mindsets do not appear to be region-dependent or even organization-dependent. Policy staff throughout the Netherlands and within organizations viewed the approach to energy poverty differently.

Finally, regardless of the current context of the research, the Q method offers a clear way to map opinions among all kinds of groups (for example in national politics, energy suppliers or among all Dutch people) on various topics. The combination with interviews proved to be crucial to nuance the mindsets.

Bibliography

- Mulder, P. Dalla Longa, F. & Straver, K. (2021). De feiten over energiearmoede in Nederland inzicht op nationaal en lokaal niveau. TNO.

- Hesselman, M., Varo, A., Guyet, R., & Thomson, H. (2021). Energy poverty in the covid-19 era: mapping global responses in light of momentum for the right to energy. Energy Research & Social Science, 81.

- Goldthau, A., & Boersma, T. (2014). The 2014 Ukraine-Russia crisis: Implications for energy markets and scholarship. Energy Research & Social Science, 3, 13-15.

- https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/ondanks-steun-is-het-aantal-energiearme-nederlanders-fors-toegenomen-isolatie-is-de-oplossing~be96f120/

- https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/ondanks-steun-is-het-aantal-energiearme-nederlanders-fors-toegenomen-isolatie-is-de-oplossing~be96f120/

- https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2023/01/07/onze-mensen-die-bezig-zijn-met-armoede-lopen-echt-op-hun-tandvlees-a4153572

- CBS https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2017/50/welvarende-paren-kwetsbare-eenoudergezinnen & CBS https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2007/17/eenoudergezinnen-in-de-bijstand-een-vrouwenzaak

- EIGE https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-equality-index-2020-report/grave-risk-poverty-harsh-reality-older-women-and-every-second-lone-mother

- Carlsson-Kanyama, A., & Lindén, A.-L. (2007). Energy efficiency in residences—challenges for women and men in the north. Energy Policy, 35(4), 2163–2172.

Iyoho, A.E., Ng, L.J., & MacFadden, L. (2017). Modeling of gender differences in thermoregulation. Military Medicine, 182(3/4), 295–303.

Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez, C., Sanz Fernández, A., & Núñez Peiró, M. (2020). Feminisation of energy poverty in the city of Madrid. Energy & Buildings, 223. - Feenstra, M. (2021) Gender Just Energy Policy: Engendering the energy transition in Europe, PhD thesis University of Twente, the Netherlands.

- De Jonge, H. (25 Mei 2022) Beroep op CW Artikel 2.27 ten behoeve van de bestrijding van energiearmoede via gemeenten.” [brief] Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.

Kuijpers, C.B.F. (3 December 2021) “Middelen aanpak energiearmoede.” [brief] Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.